About a decade ago, New Delhi-based entrepreneur Jai Dhar Gupta became a clean air activist when he was diagnosed with bronchial asthma. His motive was to spread knowledge about the need to ensure our cities breathe easy, and he was on the air pollution think tank of the Delhi Government (wherein he helped bring into effect the odd-even rule for vehicles), and also went on to found Nirvana Being, which retails air purifiers and masks.

Over the past few years, Jai has been working on yet another pet project: creating India’s first biosphere within a tiger reserve. “Rajaji Raghati Biosphere (RRB) is a 35-acre private forest initiative led by ecologist Vijay Dhasmana, who is known for restoring the Aravalli landscapes, and me. We have identified rare and endangered species of native trees, shrubs and grasses that are disappearing from these rich habitats. The project is an attempt to revive and restore some of these species, and protect the area from poachers and mining,” says the 51-year-old.

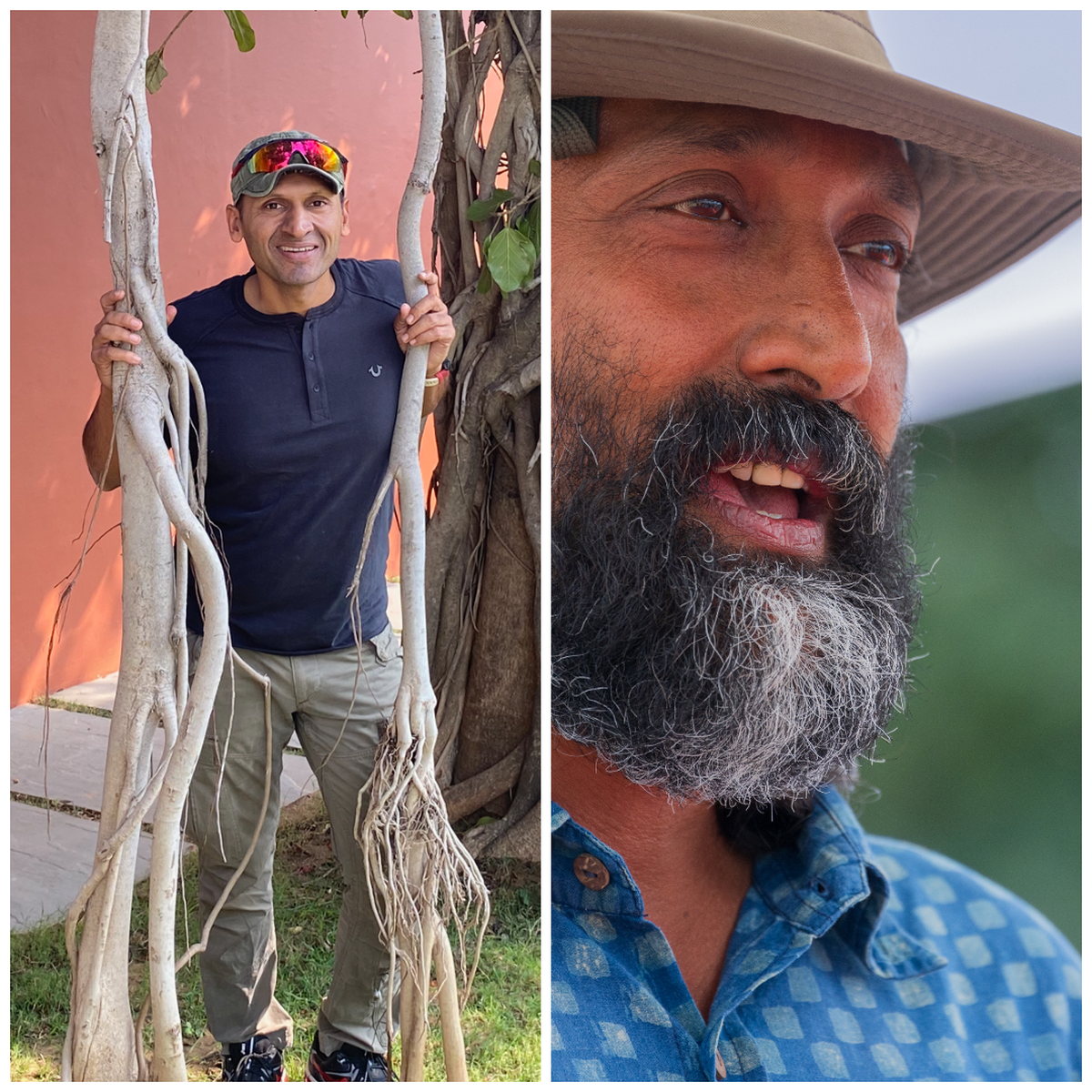

Jai Dhar Gupta (left) and Vijay Dhasmana

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Situated within the Rajaji National Park in Uttarakhand, the biosphere overlooks the rocky white Raghati riverbed, nestled in the Shivalik foothills. Taking us through the process of creating the biosphere, Jai says when they started, the land earmarked for RRB was barren and in a state of degradation. “It had been previously flattened, eroding natural contours and leading to severe soil erosion. Moreover, since monoculture agro-forestry with non-native eucalyptus trees was practised on the land, it deteriorated the ecosystem’s health further,” he says, adding, “Thousands of non-native eucalyptus trees were removed within days of acquiring the land. Subsequently, the land was contoured to retain water, prevent erosion, and promote groundwater recharge, resembling natural forest contours.”

The duo and their team conducted extensive surveys to identify suitable native plant species, especially those rare or disappearing in the region. “We collected seeds, established a seed bank, and collaborated with biodiversity parks to germinate and cultivate saplings of trees such as haldu, rohini, mala, saal, jamun, pangana, etc, which were then planted across the biosphere,” says Jai, who has also banned combustion-engine vehicles in the region, and ensures all food consumed is locally sourced.

Jai and his team conducted extensive surveys to identify suitable native plant species

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

In 2023, the duo initiated the first phase of plantation, introducing approximately 80 species. “This upcoming monsoon season, we plan to incorporate an additional 35 to 40 new species in the biosphere. However, transforming an area into a thriving forest ecosystem is a gradual process. It’s estimated to take another two to three years for the forest to truly resemble a natural habitat,” adds Jai. Once the plantation is complete, the team needs to be mindful about how the plants will interact with wildlife in the area, says Vijay. “Invasive, exotic invasives will be weeded out, and this will give chance for the late succession native species of trees, shrubs, herbs and grasses to establish themselves. The final result will be a mosaic of forest communities within the land, with self establishing and self nurturing abilities, as found in the adjoining forest patch of Rajaji Tiger Reserve,” he explains.

“The focus of this agricultural land extends beyond combating climate change to establish a harmonious model of cohabitation,” says Jai, adding that they are relying on the knowledge and skills of the local nomads called Gujjars. “They are highly sensitised to these environments and this habitat. Their objectives encompass forest cultivation, protection, restoration of indigenous flora, ecological succession, monitoring, climate research, and the establishment of carbon sinks,” he adds of the project that has been in the works since 2021.

An elephant in the Rajaji National Park

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

But, why does India need such biospheres? Jai explains how forest models such as RRB offer a promising approach not only to combating deforestation, but to growing our forests. “They showcase how local communities can effectively manage forests for conservation and economic benefit, setting a compelling example for others to emulate. We’re aiding this process in the biosphere by constantly protecting our borders and weeding out these non-native invasive species,” he says, adding, “We had always lived and co-existed with Nature and now we’ve lost that balance in our big cities. What we’re doing is not really rocket science. We’re really glorified maalis (gardeners), but with a strategic kind of vision and plan.”

Having said that, the process of getting it all together has not been easy. “Logistical hurdles like land acquisition, regulatory compliance, and long-term sustainability planning could impede the widespread adoption of the private biosphere model. We’re always under threat from the mining mafia as illegal mining is rampant and our forests are constantly looted for wood, sand and stone,” says Jai, adding “Collaborative efforts among governments, private entities, and local communities are crucial in overcoming these hurdles and realising the potential of private biospheres.”

This upcoming monsoon season, the team plans to incorporate an additional 35 to 40 new plant species into the biosphere

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Which is why Jai and Vijay are already working on a second biosphere atop the Western Ghats: above the Koyna River in the buffer zone of the Sahyadri Tiger Reserve near Pune, Maharashtra. “It has a very different habitat, different topography, and completely different flora. Since we are in a very high wind zone atop the ghats, we face a lot of issues with rainwater harvesting and irrigation, erosion of topsoil, etc.” says Jai who plans on growing Lagerstroemia microcarpa (nana), Catunaregum spinosa (gela) and Ziziphus xylocarpa (torna) among other species.

#Rajaji #National #Park #home #Indias #private #biosphere #tiger #reserve